Great Power Chessboard - How the United States seek to counter China’s Latin American reach

1921 Cartoon depicting the Monroe Doctrine - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Story_of_Mankind_-_The_Monroe_Doctrine.png

Across Latin America, Chinese investment has reshaped the map of trade, from new ports on the Pacific to mining projects deep in the Andes. Washington has realised this trend and is now asserting its own influence. Now in Trump’s second term, Pentagon lead strategist Elbridge Colby is steering a return of United States (U.S.) security focus on the Americas, a shift he calls ‘homeland first, hemisphere next.’ The plan signals a modern revival of the Monroe Doctrine, aimed at containing Chinese and Russian influence and restoring U.S. influence in its own backyard.

Washington’s draft strategy suggests a posture that turns inward. After decades of far-flung commitments in Europe, the Middle East and East Asia, the Pentagon is applying a fresh emphasis on the Americas. The plan seeks to shape the region’s politics in its favour, backing governments it sees as aligned, reliable partners such as Milei in Argentina, which in October secured a USD $20 billion financial rescue package, and supporting Rodrigo Paz, Bolivia’s newly elected, Western-friendly pro-business government. The shift also points to a harder line against adversarial regimes such as Nicolás Maduro’s in Venezuela, which remains a target for an increase in diplomatic and economic pressure. Within the language of ‘hemispheric stability’, the new approach seeks to rebuild a bloc of aligned governments across Latin America, before the U.S. returns its attention to China’s influence in the Pacific.

The man tasked with articulating this policy shift to minute detail is Elbridge Colby, the Under Secretary of Defence for Policy[--2] , He built his reputation as a China hawk after helping design the 2018 defence strategy that put deterring Beijing at the centre of American planning. In 2025, he pressed for a partial halt on weapons shipments to Ukraine in order to conserve stocks needed for a possible confrontation with China, this underscores his focus on pacing threats and balancing resources allocation. However, the new blueprint he steers today points inward instead. Colby argues that U.S. must secure its own backyard first, fortify supply lines and rebuild influence in the Western Hemisphere before it can optimise effectiveness in any Indo-Pacific crisis. Within this budding strategy architecture, the shorthand for the renewed approach is ‘homeland first, hemisphere next.’

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

The new strategy revives an old idea from Washington’s past. In the early nineteenth century, the Monroe Doctrine warned outside powers away from Latin America. Today the concept returns, with China and Russia cast as the main interlopers, some analysts label the pairing the DragonBear. The approach emphasises active measures to patrol sea lines, police illicit narcotics flows and heap pressure on unfriendly governments. Early signals include a tougher stance toward Venezuela and an attempt to overthrow the Maduro regime. The spirit resembles the 1904 expansion of the Monroe Doctrine under Theodore Roosevelt, which assert a right to intervene to protect American interests. The strategic aim now is to block durable footholds created by Chinese investment, technology exchange and port purchases; also Russian security ties and political details. While shoring up Latin American partners who align with Washington’s leadership and political order in the hemisphere.

The revival of the Monroe doctrine has a mixed reception across the region. Leaders who remember earlier U.S. dominance today call the new push interference and warn it appears neocolonial. Brazil’s Lula da Silva maintains relations with China and accepts Chinese credit, markets and equipment. Arguing his country needs investment and cannot afford to be discriminatory of where it comes from. Venezuela’s Maduro leans on BRICS partners and on Moscow for political and security backing, portraying U.S. pressure as proof that his government defends Venezuelan sovereignty. Others read the room differently. Panama has walked away from prominent Chinese Belt and Road projects after U.S. pressure[--4] . Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, faced early pressure to take a tougher stance on drug cartels, but she has resisted talk of U.S. military intervention, insisting Mexico can handle its own security on its own terms. Across Latin America a common rhetorical position is upheld, Latin America wants options, not strict bloc discipline. Most governments say they will continue to trade with both powers and refuse to be forced into a single camp.

Some strategists say the pivot away from the world to focus inwards has a logic. America cannot do everything everywhere all at once and focus on their own hemisphere promises clarity after years of drift. Yet, other strategists mention notable downsides. In Europe, allies worry that the drawdown will put pressure on their own budget due to more responsibility to fund their own security. Also, that the steady flow of surveillance data, transport aircraft and training missions that have underpinned NATO’s eastern flank could begin to thin. In Asia, partners in the U.S led alliance networks such as the Quad and AUKUS desire firm proof that Washington still intends to deter Beijing in the Pacific. Any hint of slack could give China and Russia incentive to test where new boundaries lie. Critics argue that modern security runs on connected theatres rather than exclusive concentration on any single region. A retreat in one zone radiates into others, shifting risk and encouraging opportunistic revanchism. The question hanging over the pivot is whether saved resources outweigh the credibility it spends.

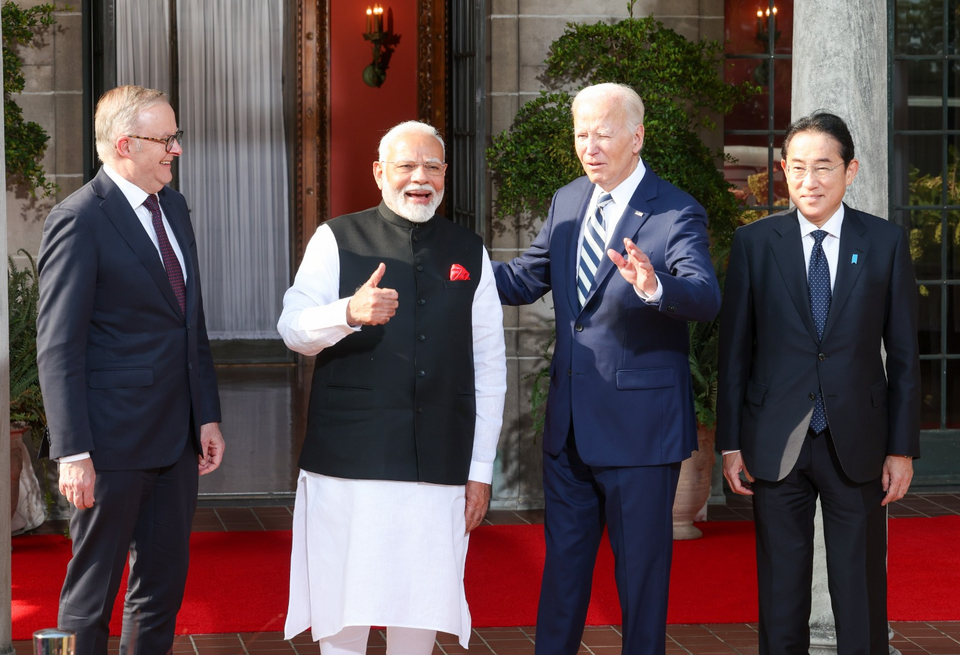

Quad Leaders at 2024 Quad Summit -

While Europe and Asia brace for reduced attention, Latin America now finds itself once again at the forefront of U.S. strategic ambition. Across the region, politics are entering a time of political realignment. Old alliances are shifting as Washington reasserts itself and Beijing’s grip on trade, energy and technology endures across the continent. In this climate, U.S. support is expected to boost governments that share its outlook. The White House is utilising financial aid and diplomatic favour to strengthen friendly governments. Security cooperation and economic deals will follow, rewarding partners that support Washington’s leadership role in the region and tightening influence through banking and security ties. The reaction is already visible. Leaders on the left frame this as instruction, insisting their countries will not be drawn into another era of American dependency. Across the region, two tendencies arise. One gathers those pulled toward Washington by money, trade and protection, while the other leans toward the looser networks of China and BRICS. Between them lie nations trying to balance both poles for leverage. The coming years reveal whether Latin America settles into one camp or becomes the testing ground of a divided world.

Content Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of the Australia Latam Emerging Leaders Dialogue.